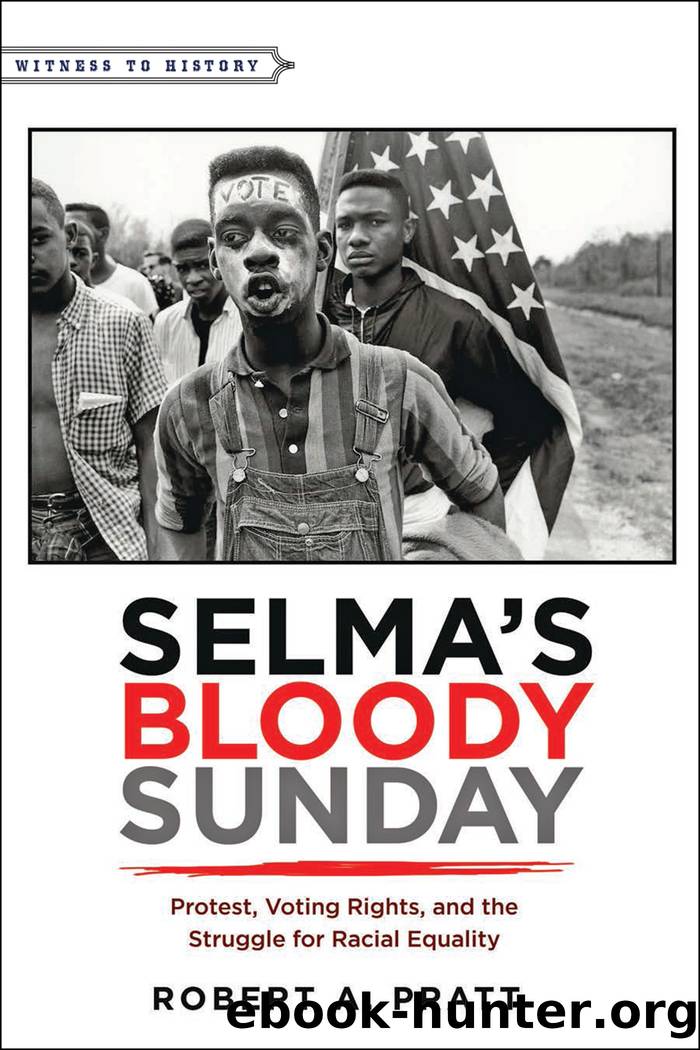

Selma's Bloody Sunday by Robert A. Pratt

Author:Robert A. Pratt

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Johns Hopkins University Press

Published: 2016-04-14T16:00:00+00:00

After federal judge Frank M. Johnson lifted his injunction and ruled that the protesters had a constitutional right to demonstrate, more than three thousand marchers set out from Brown Chapel on March 21, 1965, exactly two weeks after Bloody Sunday, heading across the Edmund Pettus Bridge en route to Montgomery. This aerial view shows the marchers as they head out of Selma. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

The marchers covered roughly seven miles the first day, and that night they rested at David and Rosa Bell Hallâs 80-acre farm. The Halls lived with their eight children in a three-room shack without indoor plumbing. Neither of them was registered to vote. Fearing retaliation, the Halls had initially hesitated when approached about allowing the marchers to spend the night on their farm. But finally they agreed. When Mr. Hall was asked if he feared for his familyâs safety, he simply remarked, âThe Lord will provide.â When seventy-five-year-old Rosa Steele was asked the same question after she agreed to allow the marchers to spend the second night on her 240-acre farm in Lowndes County, she gave a similar response. âIâm not afraid. Iâve lived my three score and ten.â31

The first night was cold, below freezing. More than two thousand of the marchers bedded down beneath three large tentsâbut first thing in the morning, most of them would have to return to Selma in a convoy of cars and buses. One of the conditions of Judge Johnsonâs order was that there could be no more than three hundred marchers on the second day, since this leg of the journey passed through a section of Lowndes County where the highway narrowed from four to two lanes. All of the marchers, however, made the most of that first evening together, building fires, clapping hands, and singing freedom songs until they finally fell asleep. For his part, King spent the first night in a sleeping bag inside a mobile van, the dayâs walking having left him with a painful blister on his left foot.

On Monday, day two of the march began uneventfully, though some of the marchers were on edge after hearing rumors that local Klansmen had hidden bombs and land mines along the route. Well known for its long history of racist violence and the numerous blacks who had disappeared or died under mysterious circumstances there, âBloody Lowndesâ County had always been of particular concern to movement activists. There were also renewed attempts to discredit King as a leader, as the marchers came upon billboards depicting King as a Communist. Allegations of this sort were nothing new. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had always maintained that King and the entire civil rights establishment were under Communist influence, accusations that had intensified in 1957 when King was photographed at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, a controversial center of progressive political activism (King had been invited to speak at the twenty-fifth anniversary of the schoolâs founding). But King and the others ignored such distractions, focusing instead on the many blacksâthose who were not part of the marchâthey encountered along the way.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19085)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12190)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8909)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6885)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6279)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5801)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5752)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5507)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5442)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5218)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5153)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5087)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4960)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4924)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4788)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4752)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4717)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4507)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)